Best and Worst Hip Flexor Exercises for Healthier Movements

Weakness in the hip flexors can lead to reduced sprint speed, lower knee drive, poor posture, decreased stability during compound lifts, and a higher risk of hip and lower back injuries. These muscles are involved in almost every lower body movement, especially in sports that require running, jumping, kicking, or quick directional changes.

Despite its importance, hip flexor weakness and imbalance are still common, even in relatively fit individuals, mainly due to our increased time sitting throughout the day and sedentary lifestyles. Research has shown that weak hip flexors are linked to reduced mobility and even serve as a predictor of health decline, especially later in life.

This article will discuss the best and worst hip flexor exercises to help you develop stronger and more functional hip biomechanics.

Training your hip flexors is essential for improving mobility, posture, and overall lower-body strength. Strong hip flexors help with movements like walking, running, and squatting while reducing the risk of injuries and lower back pain.

They also play a key role in maintaining balance and stability, especially for athletes and individuals who sit for long periods. Strengthening these muscles can enhance flexibility, prevent tightness, and improve overall athletic performance.

The hip flexors are a group of muscles that play a key role in flexing the hip, meaning they bring the thigh upward toward the torso. Their movement is essential not only for everyday tasks like walking and climbing stairs but also for athletic performance.

Strong and well-developed hip flexors help generate speed and power, especially during running, jumping, and quick changes in direction. By lifting the thigh and driving the leg forward, these muscles are vital for athletic propulsion and overall mobility.

Main hip flexor muscles:

- Iliopsoas

- Rectus femoris

- Sartorius

We’ve chosen the best and worst hip flexor exercises based on their ability to stimulate muscle growth through their ability to put the hip flexors in a lengthened position and provide optimal muscle engagement and safety.

The iliopsoas is composed of two muscles (psoas major and iliacus) that act together as the primary hip flexor.

Beyond simply moving the leg, the iliopsoas is crucial for trunk stability during everyday movements like lifting, pushing, or pulling.

For athletes, the iliopsoas is heavily involved in explosive movements like sprinting, changing direction, kicking, and hurdling. Despite its importance, it is often overlooked or trained ineffectively with passive stretches or weak isolation drills that do not match its real-life demands.

This muscle produces powerful hip flexion during high-speed actions, especially from an extended position, and also helps stabilize the spine and pelvis, making it essential for good posture and efficient movement.

This exercise is often promoted as a go-to iliopsoas isolation drill. You lie on your back, knees bent at 90 degrees, with a resistance band looped around your feet, and alternate pressing one foot out while keeping the other pulled in. It mimics a marching motion and seems ideal for targeting the deep hip flexors. The movement mirrors real-life gait mechanics and is commonly used in core and rehab routines with the intention of engaging the psoas.

However, despite how it looks, this setup falls short when it comes to effectively training the iliopsoas. Lying flat creates a posterior pelvic tilt that alters the psoas major’s alignment, limiting its ability to pull from the spine to the femur. The bent-knee position and minimal resistance shift most of the load to muscles like the rectus femoris, TFL, and abdominals.

The band also offers the most tension when the hip is already fully flexed, placing the iliopsoas in its weakest and least effective position. The burn you feel is often due to core bracing or joint compression, not true activation of the iliopsoas through its full and functional range.

One of the most effective ways to directly target the iliopsoas is by using a 45-degree incline setup. Sit or recline on a bench at this angle while loading one foot with an ankle weight or kettlebell. From this extended hip position, actively drive the loaded leg upward into hip flexion. This simple yet focused movement isolates the iliopsoas better than most traditional drills.

What makes this exercise so effective is that it starts from a lengthened position, maximizing tension on the iliopsoas. The open-chain setup also minimizes compensation from nearby muscles like the TFL or rectus femoris.

Even better, it closely mimics the demands placed on the hip during real-life movements such as sprinting or high-knee drills. As a bonus, it strengthens the iliopsoas through the lower half of its range of motion—where force production matters most.

Other great exercises for the iliopsoas muscle:

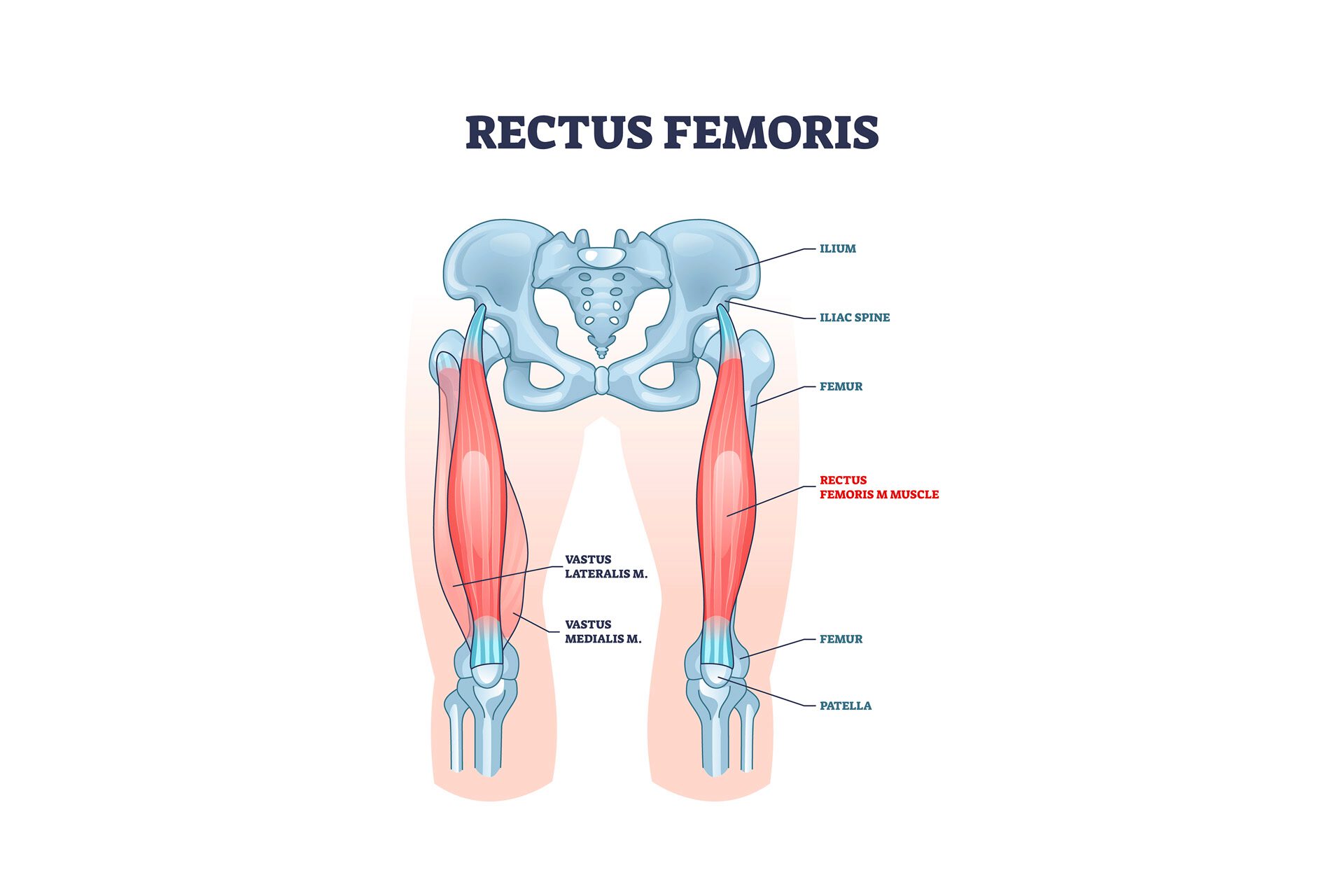

The rectus femoris is often misunderstood in hip flexor training. As one of the four quadriceps muscles, it’s unique because it crosses both the hip and knee joints. This dual action allows it to flex the hip (like when raising the thigh) and extend the knee (as in kicking or jumping).

To truly load the rectus femoris for hip flexion, the knee must be flexed or stabilized to eliminate competing tension. A better approach is to train it in a lengthened position, where the hip is extended and the knee is bent.

These movements maximize its ability to produce force while isolating the hip flexor component.

This hip flexion exercise is often used for core and hip workouts. However, it’s ineffective in properly engaging the rectus femoris because the knee remains extended throughout, keeping the rectus femoris in a chronically shortened state across both the hip and knee joints.

This drastically limits the ability of the muscle to produce force and develop more strength and size. In the end, the iliopsoas end up doing most of the work, especially in the upper range. In addition, the momentum and abdominal compensation often dominate the movement, further reducing the involvement of the rectus femoris.

While often classified as a quad eccentric exercise, this becomes a potent hip flexor drill for the rectus femoris when focused on the hip rebound. Starting in a fully extended hip and knee-flexed position, the muscle is loaded under stretch at both joints. Driving the hips forward to return to upright engages the rectus femoris through its full functional range.

More importantly, this exercise has a better performance carryover in enhancing sprint strides and explosive knee drive.

Other great exercises for the rectus femoris muscle:

The sartorius is the longest muscle in the human body, stretching diagonally across the front of the thigh—from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) down to the inner part of the tibia. While it assists in hip flexion, it's a unique case: it also contributes to hip abduction, external rotation, and knee flexion.

Because of its diverse function, the sartorius often goes undertrained or misused. Traditional sagittal-plane hip flexion drills (like marching or straight-leg raises) are usually lacking. In rehabilitation, studies have shown that to improve hip flexion function and prevent injuries, athletes must also train the rotation components of their hip joints.

To fully engage the sartorius, exercises must challenge it through hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation, often simultaneously.

The clamshell exercise is often modified with a forward hip flexion to supposedly emphasize anterior hip muscles. However, while it matches the movement of the sartorius muscle (hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation.), the movement is dominated by the glutes.

The sartorius muscle is a long and superficial muscle that works better in open-chain, diagonal movements.

This exercise mimics the sartorius’ actual line of pull and anatomical fiber orientation. It properly combines the three main movements of the muscle and creates a more athletic and functional stimulus similar to movements in pivoting, high knee sprints, and cutting corners.

Other great exercises for the sartorius muscle:

Here’s a workout plan for women:

Same for men:

The key mistake people make when training their hip flexors is working them in shortened positions—using exercises that feel hard but fail to build real strength. To train the major hip flexor muscles effectively, you need to load them through hip extension into flexion, where they produce the most force.

Don’t confuse effort with effectiveness. Choose movements that align with the muscle’s fiber orientation and apply resistance where these muscles are biomechanically built to work.